Benjamin Franklin is often quoted on tax: “In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” That isn’t true for the capitalist class.

Tax doesn’t have to be taxing – if you are the ruling class

WORKERS, MAR 2011 ISSUE

Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne will deliver his Budget on Wednesday 23 March amid the concern of most British people about what the future holds. Higher taxes, less job security, reduced welfare benefits, rising prices and fewer public services are widely expected.

The ruling class however has a different outlook. It sees that this government, like the last one, is willing to meet its demands. It expects a cap on wages even with rising inflation, restrictions on trade unions and above all to be itself insulated from the effects of the economic crisis.

Changes in taxation provide evidence that the coalition government has only the interest of capitalism as its guide. All else is lies and deceit.

Cameron, Clegg and the rest brandish slogans like clubs. They think workers are too stupid to see what is going on or too timid to do anything about it. Neither is true, though many would be surprised at the extent of the shift in the tax burden from businesses and the wealthy to workers and their families.

|

|

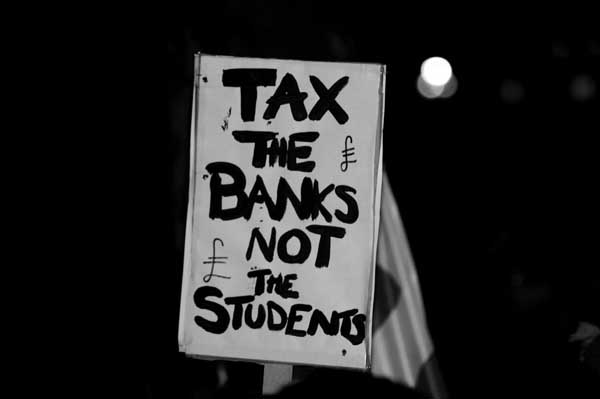

London, 9 December 2010: students get the message. Photo: Andrew Harvey/Shutterstock |

VAT went up in January, national insurance will go up in April – for workers these are unavoidable. Taxes on companies and wealthy individuals are another matter. Corporation tax is due to fall by 4 to 24 per cent. More importantly much of it can be avoided quite legally, and often is. Some of this is open and well known – such as reducing VAT and betting tax by the use of havens like Jersey or Gibraltar. An argument runs that this is good for us: it is “efficient” and keeps costs down – possibly true, but only for the companies and not their consumers.

In February Barclays Bank announced worldwide profits for 2009 of £11.6 billion on which it paid about £1.3 billion tax. But the proportion of tax in Britain was around 10 per cent – £113 million, which is completely out of line with its level of activity here. Barclays also sold its money manager offshoot, Barclays Global Investors, for over £10 billion, with a net profit on the sale of nearly £6 billion. Thanks to generous rules introduced by Gordon Brown, the tax on that was £200 million, just 3 per cent of the profit.

Late last year it emerged that a dispute between Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs and Vodafone had been settled for £1.2 billion, far less than many professional observers thought likely. The tax bill is thought to have been sliced by passing transactions through a Luxembourg subsidiary. Allegations were made about a too-soft approach by the Revenue and that the outcome was influenced by the position of the Vodafone finance director as one of George Osborne’s corporate tax advisors. But why they were using such offshore arrangements at all?

These two companies are not unusual – it’s just they have come to light. What we can see shows how multinationals can move their affairs around to minimise the tax they pay. And even that is not enough.

Britain: tax haven for the rich

Nearly all developed countries have tax rules that attempt to prevent or minimise the loss of tax in this way. At the moment Britain has such rules, but the government plans to let large business have an exemption so no tax is paid on earnings from foreign branches. They will still be able to claim overseas expenses of course – and the financial sector will be the most able to take advantage of the change.

There will be knock-on effects if the plan goes ahead. Banks and insurance companies will have a large financial incentive to move head offices out of Britain and route profits through tax havens. Any that do not follow suit will be at a significant commercial disadvantage. Other countries and sectors will then want to join in. The result will be many fewer jobs in Britain and less tax for public spending too.

Barclays chief executive Bob Diamond appeared at the parliamentary Treasury Select Committee the week before its low tax bill became public. He said that it was time to stop bashing bankers, as if somehow unfair criticism was hurting them.

When the tax figure became public his company claimed that they contribute £2 billion in tax, but did not point out that most of that was in payroll taxes, in other words deductions from their workers’ salaries. Nor did it admit that the most highly paid individuals have ways of avoiding tax through complex legal schemes that mirror those used by companies.

Some of this has been exposed and there are suspicions about other ways companies avoid paying tax. But it is hard to find out more about what is happening, because companies are allowed to hide information about where they pay tax.

You can find out the pay of senior civil servants or hospital administrators, but you cannot find out even basic information about the tax contribution of most well known companies operating in Britain. We are deluged by superficial “transparency” initiatives about crime figures or school performance, but banks and others are not compelled to report country-by-country on where they make their money and where they pay tax.

Propping up profits

The public purse is used to prop up capitalist profits, but never the other way round. The classic defence is that companies must act in the interests of their shareholders and so must indulge do everything legal to minimise their tax bill. That argument is kept quiet when taxes on workers are raised to pay off the public money used to bail out banks and deal with the outcome of the financial crisis.

Even Barclays (which did not take a government bailout) gained from support for the banking system in 2008.

Alternatively companies argue that what is good for them is good for the country; even if it seems “unfair” they don’t pay much tax. That is untrue in many ways – it ignores the international way that capitalism uses tax advantages. Ireland and other European countries have tried low tax regimes to attract investment, and they are abused and abandoned whenever it suits the “investors”.

Meanwhile, the people living in tax havens like Cayman or the British Virgin Islands see very little of the vast wealth that flows through their offshore financial regimes. At worst it encourages corruption and criminality to protect that status. And it distorts the economy of countries where profits are generated.