It is time to forget the fads and the political play fighting. Get back to the workplace...

Trade unions – dead or alive?

WORKERS, APR 2012 ISSUE

On 1 December 2011 a sub headline in the London Evening Standard newspaper decried: “Barely a million take strike action.”

Barely a million – this was genuinely written as if to dismiss the biggest strike in a generation, when well over a million public sector workers took strike action to protect their pensions on 30 November. This was easily the biggest show of union strength since the “winter of discontent” and possibly since 1926.

But while the numbers are indeed impressive, and the attempt to belittle this demonstration of collective organisation ridiculous, another story is told if the number is converted into a percentage of all those entitled to take action.

Had the Evening Standard said only 35 per cent took strike action it would look quite different. A third take strike action doesn’t sound half as good as a million. So why is this important? Because 30 November was a paradox. On the one hand it was collective organisation in action, but on the other it showed that this action was not absolute, resolute or sustainable. The strike and its aftermath illustrate where unions are today.

State of the unions

The current balance sheet is not good for unions. We have a declining membership and massive cuts in traditionally unionised areas – a membership fearful, demoralised and apathetic. Unions are continually subject to a media hate campaign. They endure straight hostility from the Coalition and indifference from the party in opposition. Trade unions operate in an almost fascist legal environment where every action is scrutinised and subject to the courts’ interpretations.

RMT banners on Tyneside during the November action on pensions.

Photo: Stephanie Delvin

On the plus side Britain still has over 10 million workers organising themselves within their workplaces. Union membership is worth 20 per cent more in pay.

In 2010 the average hourly rate was £14 for union members; £12 for non-union members.

Professionals join unions – much more than do the lowest paid. Those that need most to act together are being picked off by employers and left marginalised by the lack of collective bargaining. 2010 statistics show a trend that membership levels have settled but collective bargaining is dying. Less than a third of employees are covered by collective agreements, with significantly fewer – 16 per cent – in the private sector and around 65 per cent in the public sector. But the past decade saw a fall of 10 per cent during a time of expansion in public sector jobs and improvements in union–government relations.

Too big to fail?

Unions are sitting targets without the flexibility or agility to respond to disputes or attacks from employers or government. The sheer effort it takes to avoid Tribunal or Certification claims means unions are defensive and bureaucratic.

The consequences of breaching the draconian trade union laws are such that a union is rightly terrified. Sequestered funds means bankruptcy. For all the cash ferried round in 1984 during the miners’ strike, the fact is now a union would collapse and people would end up in jail for money laundering.

Despite the rhetoric in the mission statement of Unite, the bigger the union the less coherent the thread of solidarity that runs through the disparate and fragmented membership.

The corporate behaviour of SEIU, the US-based Service Employees International Union, or even of Unite, is the antithesis of the movement. In the quest for expansion the organisations are over-reaching, tearing apart the very fabric that made the body strong to start with. It is fatal. But they want to become bigger still. Unite–PCS? UCU–NUT? Union mergers fuelled by ultra left fantasists.

A whole body of academics, think tanks and trade unionists pontificate and conjecture about the future of the movement. Too many start at the highpoint of TU membership – 12 million in 1979 - and ask how to survive this fatal decline – 6 million at present. Very few actually ask the simple question: How did we have 12 million members in 1979? What drove this and was it sustainable in a changing Britain? The movement originated at a time when the act of membership was a crime, and burst into life, becoming a political and industrial force at a time when strikes were unlawful.

But now fad and fashion have taken hold across unions, TUC and academics – even in research. The claim is made that the main reason people have not joined a union is that they haven’t been asked. Really? Anyone who has spent any time talking to non-members will know this is rubbish but it is part of the myths that have kidded much of the movement. Most of the people answering the question in this research are in non-unionised workplaces. So the real answer is because there was no union in my workplace.

The insurance approach

This obsession with arresting decline led unions to adopt an employee insurance approach. The attempt has backfired as too many members see the union as a cheap legal service and the weight of European laws has forced ever more disputes into the courts and out of the workplace.

Belatedly unions have recognised that a service-based model is bad for members and bad for the organisation. But in its place is the new fetish called organising, and in this unions tend to look abroad: the wrong answer to the wrong question.

Take the SEIU. What on earth can we learn from a US organisation that is the product of ruthless corporate unionism still numbering only 2 million members, in a country with a 300 million population? Britain has 65 million people, and its biggest union is 1.4 million strong. As a percentage of the population, Unison has 2 per cent of the population, while SEIU has 0.75 per cent. Yet we are seeking lessons from them?

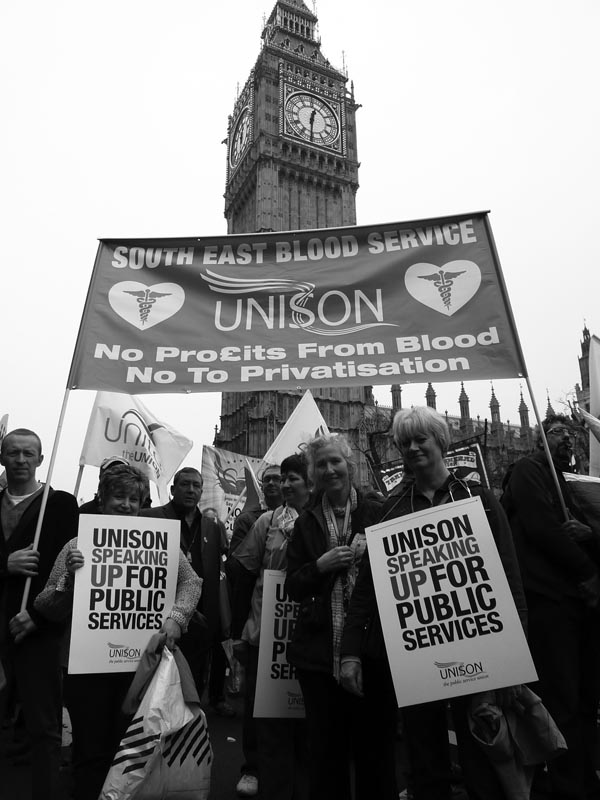

London, 12 March 2012: Demonstrating for pensions.

Another buzzword of the moment is community organising. We’ve failed to use our inherent strength through the workplace and demonstrable through collective action? Instead, let’s pop round to the vicar and ask him to write a letter about cuts. If a union is strong and organised in the workplace it will de facto play a role in the community.

Unions are 19th-century organisations in a 21st century world. We should be proud of our traditions but free ourselves from dated language in communications. Members rarely read letters or newsletter from their union so using mass media is essential. And presentationally the unions have far to go. Unions constantly allow the media to set the terms of the debate and very rarely know how to rebut the lies and spin. Few unions have a genuine media strategy or even understand the media.

The same is true for IT and the web. But in the rush to seem trendy and relevant unions have jumped on a social media bandwagon without understanding the lack of control. Technology is a great tool but discipline is hard to maintain when everyone is on Twitter or blogging within seconds of any action, meeting or event. If you followed Twitter about pensions you would have had the strangest impression about who belongs to unions and why! The vast majority of union members still gather information from the broadcast media, not their union.

Whatever its weakness the 30 November action was an awesome display of strength that forced the government to shift. It wasn’t outright victory but clearly not a defeat or a capitulation, as so many mad ultras would have you believe.

But the episode is a good example because it demonstrates once again that the activist base in so many of our unions is dominated by the naysayers and the impossibilists that engender demoralisation and reinforce the notion that unions are weak. It is these so-called fighters and militants that are strangling the unions.

Roughly a third of union members took part in the ballot. Most agree that it was just above half the membership taking action. This means that with membership density rarely above 50 per cent we had 1 in 4 employees on strike.

Anybody who spent time with workers on the ground knew that workers were resistant to striking. When convinced as to why we had to they were clear that sustained action would not be achieved through lots more days of action.

The government position had hardened after the strike in June as they could sense victory. But they overplayed their hand and spent much of November trying to return to where they had been – why? Because now there were millions about to walk out.

It also helped that the government was incapable of recognising the difference between the schemes. This inability ensured the employers were silent. The employers played a major part in the dispute but for the most part it was in the unions’ favour.

When the Treasury publicly supported the unions' Heads of Agreement, it was announced that attempts to introduce 50 per cent ballots would be shelved and other consultations would be revisited.

But this wasn’t a concession. It was a tactical withdrawal. The government knows the laws are so tight that to tighten further will mean workers break them with or without unions. This is the lesson from every anti-trade union law. Eventually the workers will break the chains.

This government was not able to go to war with unions – despite its hopes – and workers showed genuine strength.

To call for a continuing “rolling programme” of strikes is weak and self-defeating. We have to be smarter – conserve our forces and fight were we are strong on the ground.

Some union leaders want to be commentators on the Westminster theatre rather than participants in the industrial struggle. When they forced the issue over the Labour leadership, to choose between Milibands, they found they had installed a puppet with faulty strings. The same old cries of why fund the Labour Party etc spring up, but not a single union is seriously looking into cutting links. The Labour Party has infiltrated the union movement.

The terms of political discussion are dominated by more fads and identity politics. Real politics is on the shop floor, the factory canteen and the open-plan office.

Workers will organise themselves whatever we call the organisation. Wages, hours and safety were and remain the driving issues for the working class.

The local workplace is the most effective unit to build solidarity and purpose. In the workplace workers can bargain together, resist attacks together and defend each other.

So it is time to forget the fads and the political play fighting. Get back to the workplace. Build and develop solidarity at the most local level to the members. ■