Financial speculation, irresponsible behaviour in the City, massive government debt, shares slumping: three centuries ago, finance capital was learning its tricks…

The rise and fall of the South Sea Bubble

WORKERS, SEPT 2009 ISSUE

Ruinous financial speculation and bursting bubbles are not new, having happened many times before, occurring as early as the 17th and 18th centuries. Far from being unaccountable accidents, they are a characteristic and a feature of the economic cycle of the capitalist system.

Take for example the South Sea Bubble, one of history’s earliest and worst financial bubbles.

By 1710, London had already become the kingdom of the “moneyed-men”, and early signs of financial recklessness could be detected. The stockjobbers, who resided in a series of narrow passageways called Exchange Alley, located by the intersection of Cornhill and Lombard Street, were actively involved in the buying of stocks and shares, but there was a prevailing sense that ‘shares will go ever upward’.

In the saying of the day, the dealers’ aim was “to sell the bear’s skin before they have caught the bear”. Enterprises were founded on little more than an encouragement of human greed and corruptibility.

The greatest scheme was the South Sea Company (established in 1711 by the Lord Treasurer, Robert Harley) which was granted exclusive trading rights in Spanish South America.

Debt

In 1710 the Tories had taken power from the Whigs. There was a huge government debt of £10 million, and borrowing money from the Whig dominated City was difficult. Harley wanted to provide a mechanism for funding government debt incurred in the course of the war.

|

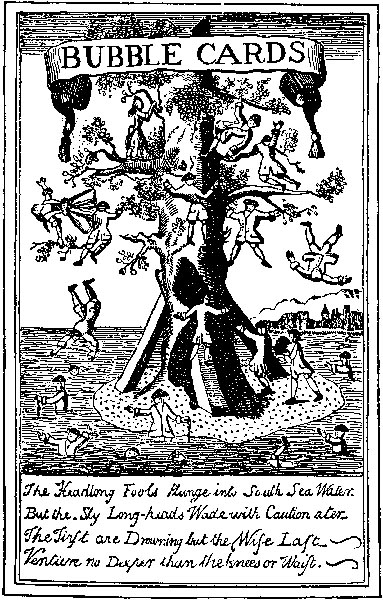

| Playing cards mocking the Bubble became fashionable in the 18th century. |

But Harley could not establish a bank, because the charter of the Bank of England made it the only joint stock bank. He therefore established what, on its face, was a trading company, the South Sea Company, though its main activity was in fact the funding of government debt.

The mania started in 1711. Government proposed a deal to the South Sea Company, where Britain’s debt would be financed in return for 6 per cent interest. Britain added another benefit to sweeten the deal: exclusive trading rights in the South Seas, which were expected to prove enormously profitable. The company planned on developing a monopoly in the slave trade.

Additionally, it was thought that the Mexicans and South Americans would eagerly trade their gold and jewels for the wool and fleece clothing of the British. Most of these trading plans did not materialise. The South Sea Company issued stock to finance operations and gain investors. Shares were quickly snatched up from the start.

The South Sea Company, seeing the success of the first issue of shares, quickly issued even more. Investors had no quibble, despite the highly inexperienced management team. All they saw was that the stock was going to the stratosphere. Many investors were enamoured by the lavish corporate offices that had been set up, painting an image of success and wealth. It became extremely fashionable to own South Sea Company shares.

Thousands of other projects were launched in this age of the moneyed men. Speculators were known as “projectors”. They wanted money for a host of things, including “for a wheel of perpetual motion”. Many schemes were swindles or hoaxes, which were spread by greed.

Newspapers reported zealously and daily the changing prices of shares: the gullible felt a new way to make money without toil had arrived. Fortunes it appeared could be made overnight.

In 1720 a bill was passed enabling people to whom the government owed portions of the national debt to exchange their claims for shares in company stock, and shortly the directors of the South Sea Company had assumed three-fifths of Great Britain’s national debt – some £9 million.

The bill triggered an enormous burst of speculation in company stock – shares rose in value. Also, in 1720, in return for a loan of £7 million to finance the war against France, the House of Lords passed the South Sea Bill, which allowed the South Sea Company a monopoly in trade with South America.

In 1720 the whole of England became involved with what has since become known as The South Sea Bubble. The company then talked up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World, which was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy".

The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720 to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme’s acceptance, to £550 at the end of May. The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 a share to almost £1,000 a share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy as all types of people – from peasants to lords – developed a feverish interest in investing; in South Seas primarily, but in stocks generally.

Shares immediately rose to 10 times their value, speculation ran wild and all sorts of companies, some lunatic, some fraudulent or just optimistic were launched. For example, one company floated was to buy the Irish Bogs.

The South Sea price finally reached £1,000 in early August and the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, dropping back to £100 per share before the year was out, triggering bankruptcies and short selling. The bubble had burst.

Vast numbers of investors were entirely ruined. The stocks crashed. Porters and ladies’ maids who had bought their own carriages became destitute almost overnight. The clergy, bishops and the gentry lost their life savings; the whole country suffered a catastrophic loss of money and property. Suicides became a daily occurrence. The gullible mob whose innate greed had helped feed the mass hysteria for wealth, demanded vengeance.

Arrested

The South Sea Company Directors were arrested and their estates forfeited.

By the end of September the company failures now extended to banks and goldsmiths as they could not collect loans made on the stock, and thousands of individuals were ruined (including many members of the aristocracy). Parliament was recalled in December and an investigation began.

Reporting in 1721, the investigation revealed widespread fraud amongst the company directors and corruption in the Cabinet. Among those implicated were the Chancellor of the Exchequer, the Postmaster General and other Ministers. Some were impeached for their corruption; the Chancellor was imprisoned.

The events of 1720 caused suffering across the land. England at its most corrupt became the target of satirists, principally the ruling classes and the elected politicians (462 members of the House of Commons and 112 Peers were implicated). King George I and his two mistresses were heavily involved and publicly blamed.

When reality returned, the old industries of shipping, farming and landownership, too dull for the exciting times of the stock-market rollercoaster, were the places to put hard cash.