Our ninth article to mark the 40th anniversary of the CPBML by looking at the past four decades through the eyes of Workers and its predecessor, The Worker. This month: Opening the debate on migration…

2000: Nothing free about the free movement of labour

WORKERS, OCTOBER 2008 ISSUE

|

The subject of migration– both immigration and emigration – is one that many on the so-called left refuse to deal with. Yet it is an issue that won’t go away. In this groundbreaking article in November 2000, Workers took the issue head on. Who benefits? Not the workers here, and not the countries where the migrant labourers come from, either.

“Modern capitalism sees national boundaries as inconvenient irritants, restricting their right to do what they want. The ‘free’ movement of global labour is part of the capitalist dream embodied in the EU. The ideal is a single market in goods and people in which capitalists can make and sell their goods wherever they want unconstrained by national governments. They can then take their pick from a rootless, unorganised workforce which moves at their behest, lacking the power to determine pay and the conditions of their work and lives.

This is the reality of the Global Market we are asked to revere, fear and accept as inevitable as the world of the future: a world in which the balance of power between capital and labour, which swung in our favour in Russia in 1917, swings back to the capitalist class.

A number of factors have driven the worldwide rise in mass migration. Wars and economic hardship, together with the deprivation and dislocation brought about by capitalism in eastern Europe, combine with the relative ease of travel and speed of global communications. This in turn enables movement from country to country to seem more desirable and become more possible. These movements have profound effects on the countries people move to and on those they leave behind.

In Britain, the movement of foreign labour into the country enables employers to keep wages low in professions such as teaching and nursing. The acute shortage of teachers of certain key subjects and in the more difficult schools is glossed over by the practice of employing teachers from abroad on supply (non-permanent) contracts, paid rates set by the agencies which employ them. Teaching in London, one of the most expensive of capital cities, is now officially classed as a shortage occupation for immigration purposes, meaning that schools applying for work permits for non-European teachers (European are not so keen to come here) no longer need to show that they have been unable to employ a British teacher.

In nursing, some posts are extremely difficult to fill at present salaries in inner London hospitals because nurses would either need to have expensive inner London accommodation for their families or to travel to their shifts at difficult times for public transport. These jobs are often filled by nurses from abroad, with women living in digs and sending money home to their families.

Indian stonemasons allowed into Britain under the new Home Office relaxation of regulations to work on a Hindu temple in north London are being paid £3 a day…they are now demanding the British minimum wage, an increase of about 1000%!

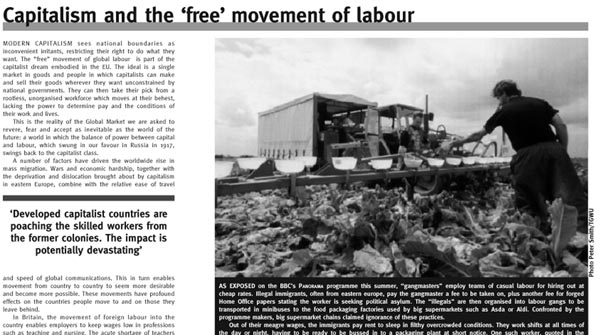

The high rate of exploitation of these legal workers is multiplied many times with illegal immigrants. As we reported in WORKERS last year, they form an important part of the labour force of agricultural gangworkers who pack supermarket goods in the countryside of Scotland, East Anglia, Lincolnshire, Kent and Sussex. The TGWU Agricultural Workers trade group has exposed their plight: working long hours for tiny wages in often dangerous and unhygienic conditions. Their illegal status makes them unlikely to protest or join a union, and their low wages are used to intimidate other, legal, workers.

Lift all restrictions?

So, in Britain, is the answer to illegal immigration to lift all restrictions, to allow in anyone at all who wants to come and live here? Immigrant workers make it easier for employers to worsen pay and conditions for workers here, but what of the effects on the countries they leave?

|

According to UN figures, almost one-third of skilled African workers had emigrated by the late 1980s – 60,000 high- and middle-ranking managers leaving for Europe and north America in five years by 1990. During that time, Sudan lost 45% of its surveyors, 30% of its engineers, 20% of its university lecturers, and 17% of its doctors and dentists. 60% of Ghanaian doctors practise abroad.

The member states of the EU which are the intended destination for these people have mass unemployment, yet the UN Commission on Population has said they need to take 75 million immigrants by 2050 – to keep up their populations or to maintain high levels of unemployment? What’s wrong with national long-term planning to ensure the supply of educated and skilled workers needed by a modern economy? All those who live and work (or want work) in Britain should be included in such a plan.…

Capitalism won’t pay

…But British workers who produce the wealth which pays for the system through taxation cannot support by their labour unlimited numbers of extra citizens who come here, wittingly or unwittingly, in the interest of the ruling class. Is capitalism offering to pay for the maintenance of people they have displaced from their own countries and lured to others? Of course not.

Eventually, nations have to grapple with their own problems, however difficult and painful. Here in Britain we have to deal with our capitalist class which wants to give up our sovereignty to Brussels. Every independent nation has a democratic right to determine what and who crosses its borders in either direction. If we allow capitalists to decide, you can be sure that workers will be the losers both here and in the developing countries.”